With characteristic capitalization, G.W.F. Hegel once observed that History can sometimes seem nothing more than a “slaughter-bench,” an altar upon which human lives – and ideals – were sacrificed. While modern historians have (mostly) put Hegel’s search for the world spirit aside, the work of studying the past remains a grave business. How could it be otherwise, when you’re reading dead people’s mail for a living? The trouble, though, is figuring out how we might make a game of it.

It’s undeniable that death, war, famine, and, yes, pestilence, are grist for the historians’ mill. The most lauded works in the field are on failures of human kindness against fear and power, memories of massacre, systems of manufactured exploitation, and empires of slavery – and that’s just the last two years of Bancroft prize winners. Economics may more commonly wear the mourning clothes of a “dismal science,” but the historical profession has a strong claim to a gloomy aspect, too.

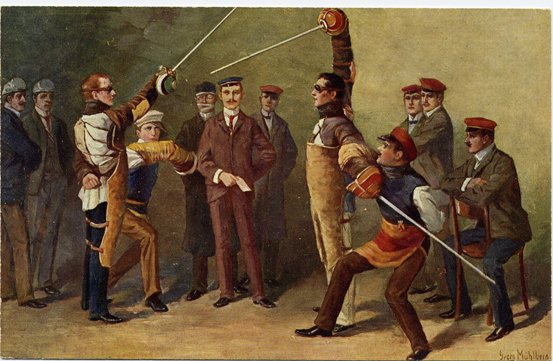

Moreover, as Hegel’s students may have noted between sabre duels and beer toasts, the dour mien of many researcher’s topics is matched to a different kind of professional seriousness, the unsmiling cut-and-thrust of academic debate. Formalalized adversarial contention, in seminar rooms and peer reviews, is widely understood as necessary for the maintenance of rigorous disciplinary standards, within history and beyond. While today’s students and professors may no longer sport dueling scars with pride, more than a touch of the Thuringian university spirit lingers on in contemporary academic conventions.

All of which poses a bit of a dilemma for us here at the Pox Hunter’s Lancet. If it’s all such a serious affair – and surely the history of infections disease must be counted within that category – how can we play games with history? It’s a question that cuts to the quick of the Pox Hunter project faster than a German duelist – and not just in terms of tone, but also with regard to analytic rigor and standards. If researching the past demands a serious and detailed attention (and it does), how in Herodotus’s name can building a video game, much less playing one, be justified as part of the enterprise? Or turned around: is there anything about play, and specifically, about play in structured environments like games, that can contribute to new insights about the world of the past?

Perhaps. To start getting at why building and playing video games may be work worth pursuing as part of a research agenda, this week at the Pox Hunter’s Lancet we’re going to look at some of the different ways scholars have engaged with video games, and consider how play might serve a role in historical work.[1]

How Have Scholars Approached Video Games in Research?

As Objects of Analysis

First and perhaps most simply, historians and historically-minded writers have approached video games as objects of analysis, technological phenomenon or cultural events whose creation or consumption requires contextualization. The literature here is perhaps best developed on the topic of wargaming and role-playing games, though it tends toward pop-history journalism or informal academic writing rather than peer-reviewed work. Among other venues, the University of Michigan Press’s digitalculturebooks imprint hosts a book series on “Landmark Video Games,” creating a canon of both historic games and historical criticism.

More rarely, the events and cultures constructed by players within in video games themselves serve as the subject of historical analysis, as in tech journalist Andrew Groen’s forthcoming (and kickstarted) book, A History of the Great Empires of Eve Online, or public historian Josh Howard’s work on oral histories of MMOs.

But the history of video games – or within video games – is not the most popular way to approach the medium. Instead, the most prolific area of academic and extra-academic commentary connected to games and game-playing is the critical analysis of commercially-produced games. Paralleling television and film criticism, games criticism is a crowded, popular genre, encompassing enthusiast discussion boards and hobbyist press reviews as well as academic studies in journals and monograph series.[2] Treating games as texts or text-like cultural products, scholars attempting this approach have used a variety of critical lenses, but share methods similar to those used to approach other media, treating the game as a textual object (or set of textual objects) fit to be deconstructed, historicized, analyzed, contextualized, etc.

While video game criticism among historians still largely finds a place outside of the mainstream of the discipline – on blogs (ahem) and magazines rather than in journals or monographs – the ways that historians have examined games follows patterns similar to how have engaged other audio-visual media like film or television.

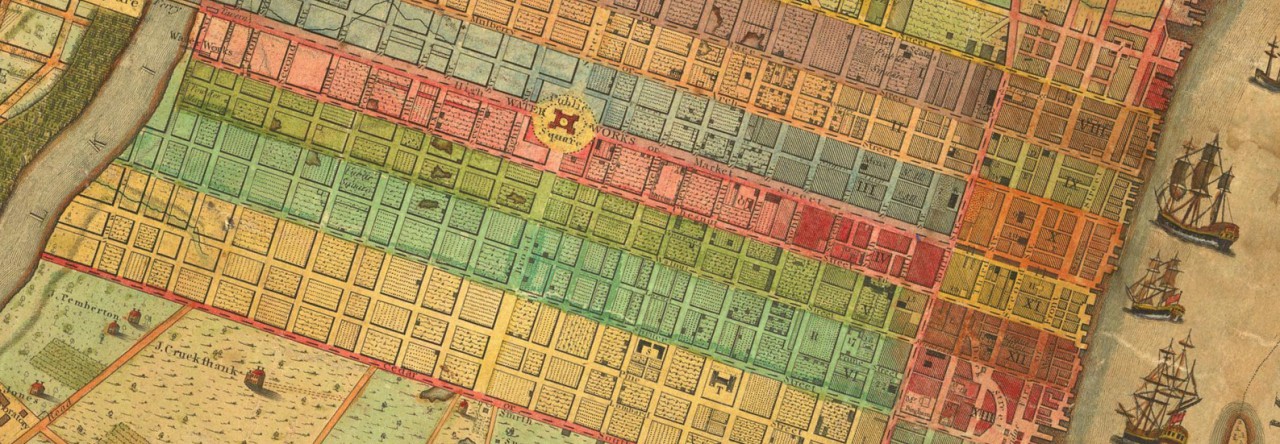

Evaluating a given game’s accuracy is a common mode of proceeding. The 2013 release of Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag, for example, set players loose in the golden age of piracy in the Caribbean – and it quickly sparked a debate over whether it was “good history,” including discussion over the game’s depiction of slavery and slave resistance. This conversation was made all the more interesting because the game’s model for the social dynamics of 17th-century buccaneering seems to have been largely animated by a ersatz version of historian Marcus Rediker’s approach to the history of piracy.

However much scholarly analysis of video games has hewed to models developed for other visual media, there are also wrinkles unique to games analysis. Media scholar Adam Chapman has usefully argued that critical approaches to games must do more than merely examine their narrative or audio-visual content, but also engage with their peculiar form, a rubric that includes genre, design, mechanics, systems, and player response and reception as well as surface “content.” Doing so, Chapman argues, will help reveal the historical assumptions and causal models underlying a given game’s systems or mechanics, while also making them comparable to other works. But this approach has the benefit of focusing on part of what makes games media unique as cultural products – the interaction between design and player that allows them to create a kind of experiential contingency that linear or non-systemic narratives do not.

The rewards of this approach are already being realized in games criticism, allowing us to move beyond a simple evaluation of accuracy and into more complex analyses. Troy Goodfellow’s series on “national character” in strategy games, a set of meditations on the representation of historical realities in faction design, provides one example of this kind of systemic analysis.

More orthogonal approaches have succeeded as well. On the surface, the game Shadow of Mordor, set in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, would not seem to lend itself to historical analysis; but by analyzing some of its player agency mechanics, Austin Walker’s analysis reveals its resonance with other debates about the depiction of slavery in games. Similarly, Peter Christiansen’s analysis of the ideological systems embedded in the mechanics of Crusader Kings II, suggests that the contingency and non-linearity of the medium can give expression to historical perspectives unavailable in other media.

Of course, analysis of a video game as a cultural production, event, text, or system does not exhaust the possibilities of the medium’s interaction with research; in the next post, we’ll take a look at how games might serve as a mode for making or developing arguments, as well.

[1] NB: for the purposes of this post, I will be leaving the teaching possibilities of games or games playing unaddressed in order to focus on research. In large part, this is because the case for including games and play in the teaching toolkit is less of a intellectual puzzle – learning games are a regular feature of many historical education models, and indeed, the use game mechanics (particularly reward systems) to structure incentives within existing teaching – “gamification” – has been somewhat of a growth industry in the last few years, if a controversial one. That said, teaching will form a topic for this blog later in the year.

[2] The situation has been complicated by the emergence politicized enthusiast groups that are aggressively opposed, sometimes even violently so, to academic or pop-academic criticism in the medium, particularly those inflected by critical feminist or race theory – an issue bigger than we have room for here, though a situation worthy of study in its own right.

Pingback: Why Play with History? Part II | The Pox Hunter's Lancet